Bluegill

Lepomis macrochirus

What do they look like?

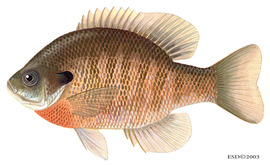

Like other sunfish, bluegill have very deep and highly compressed bodies. In other words, they are "tall" and "flat." They have a small mouth on a short head. The dorsal fin is continuous, with the front part spiny and the back part soft and round with a dark smudge at the base. The tail fin is slightly forked but rounded. The body is mainly olive green with yellowish underneath. Their name "bluegill" comes from the iridescent blue and purple region on the cheek and gill cover (opercle). A close look reveals six to eight olive-colored vertical bars on the sides.

Typically, adults are between 10 and 15 cm but they can grow as large as 41 cm.

Young bluegill are a paler version of the adults, usually silver with a slight purple sheen. (Froese and Pauly, eds., 2002; Murdy, et al., 1997; Williams, 1996)

- Other Physical Features

- ectothermic

- heterothermic

- bilateral symmetry

- Sexual Dimorphism

- sexes alike

-

- Range mass

- 2.2 (high) kg

- 4.85 (high) lb

-

- Range length

- 41.0 (high) cm

- 16.14 (high) in

Where do they live?

This species is native to lakes and streams in the St. Lawrence, Great Lakes, and Mississippi River systems. Thus, it ranges from Quebec to northern Mexico. However, it has been introduced widely in places such as Hawaii, Africa, Asia, South America, and Europe. (Froese and Pauly, eds., 2002; Murdy, et al., 1997)

- Biogeographic Regions

- nearctic

- palearctic

- oriental

- ethiopian

- neotropical

- oceanic islands

What kind of habitat do they need?

Bluegill prefer to live in lakes and slow-moving, rocky streams. They can often be found in deep beds of weeds. In Hawaii they primarily inhabit reservoirs. Though they are freshwater fish, they can tolerate some saltiness and are present in tributaries of the Chesapeake Bay. (Froese and Pauly, eds., 2002; Murdy, et al., 1997)

- These animals are found in the following types of habitat

- temperate

- freshwater

- Aquatic Biomes

- lakes and ponds

- rivers and streams

- Wetlands

- marsh

How do they reproduce?

Males make nests in colonies with from 20 to 50 other males in shallow water less than 1 m deep. The nests are circular shallow depressions, about 20 to 30cm in diameter, in sand or fine gravel from which the male has fanned all debris.

Once his nest is made, a male waits in it and grunts to attract females. When one enters, both male and female swim in circles. Eventually they stop and touch bellies, the male in an upright posture and the female leaning at an angle. They release eggs and sperm and then start the process again by swimming in circles.

A female deposits her eggs into several nests, and a male's nest may be used by several females. (Murdy, et al., 1997; Williams, 1996)

- Mating System

- polygynandrous (promiscuous)

Spawning occurs when water is between 17 and 31 degrees C; in the Chesapeake Bay area it can begin when water temperatures reach 12 degrees C. Females can carry up to 50,000 eggs which take several days to hatch. After a week, young leave the nest. (Conservation Commission of Missouri, 2002; Murdy, et al., 1997; Williams, 1996)

- Key Reproductive Features

- iteroparous

- seasonal breeding

- gonochoric/gonochoristic/dioecious (sexes separate)

- sexual

- fertilization

- oviparous

-

- Breeding season

- Breeding occurs from May to September (Chesapeake Bay).

-

- Average number of offspring

- 50000.0

-

- Average time to hatching

- 3.0 days

-

- Average

- 7.0 days

-

- Average time to independence

- 3 days

-

- Range age at sexual or reproductive maturity (female)

- 1.0 to 2.0 years

-

- Range age at sexual or reproductive maturity (male)

- 1.0 to 2.0 years

Males guard nests both before and after females lay eggs. Paternal care involves fanning the eggs and chasing away predators. (Murdy, et al., 1997; Williams, 1996)

- Parental Investment

-

pre-fertilization

- provisioning

-

protecting

- female

-

pre-hatching/birth

-

protecting

- male

-

protecting

How long do they live?

Bluegill typically live 4 to 6 years but can reach 8 to 11 years old in captivity. (Froese and Pauly, eds., 2002; Williams, 1996)

-

- Range lifespan

Status: captivity - 8.0 to 11.0 years

- Range lifespan

-

- Typical lifespan

Status: wild - 4.0 to 6.0 years

- Typical lifespan

How do they behave?

Bluegill are most active at dawn. During the day they stay hidden under cover, and they move to shallow water to spend the night. Schools may contain 10 to 20 fish. (Williams, 1996)

- Key Behaviors

- natatorial

- crepuscular

- motile

- sedentary

- social

Home Range

Home ranges of bluegill are less than 30 square meters. (Williams, 1996)

How do they communicate with each other?

Males change color during breeding season so it seems likely that visual cues are important either to other males or to females. Grunting is involved in courtship.

What do they eat?

The very small mouth of this fish is an adaptation to eating small animals. Bluegills are carnivores, primarily eating invertebrates such as snails, worms, shrimp, aquatic insects, small crayfish, and zooplankton. They can also consume small fish such as minnows and plant material such as algae. Young bluegill eat worms and zooplankton, staying under cover while adults feed more in the open. (Froese and Pauly, eds., 2002; Murdy, et al., 1997; Williams, 1996)

- Primary Diet

-

carnivore

- eats non-insect arthropods

- Animal Foods

- fish

- insects

- mollusks

- aquatic or marine worms

- aquatic crustaceans

- zooplankton

- Plant Foods

- algae

What eats them and how do they avoid being eaten?

Bluegill travel in schools and come into shallow water only at night. During the day they try to remain hidden. (Williams, 1996)

-

- Known Predators

-

- great blue herons (Ardea herodias)

- belted kingfishers (Cercyle alcyon)

- raccoons (Procyon lotor)

- brown trout (Salmo trutta)

- largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides)

- striped bass (Morone saxatilis)

What roles do they have in the ecosystem?

Bluegill are an important prey species for larger fish predators. They also impact insect populations by eating aquatic larvae.

Do they cause problems?

Several countries where this species has been introduced report that it causes ecological problems. Bluegill overcrowd and stunt the growth of other fish and may even be responsible for causing extinction of a native fish in Panama. It is considered a pest in its introduced range.

How do they interact with us?

This is an important game fish in the United States. Bluegill are fairly easy to catch and are good to eat. They are also used to stock rivers and lakes with food for largemouth bass, another important game fish.

- Ways that people benefit from these animals:

- food

- ecotourism

Are they endangered?

Bluegill are abundant in their native range. Many individuals are raised in aquaculture facilities and used to stock waterways. (Conservation Commission of Missouri, 2002; Williams, 1996)

-

- IUCN Red List

- No special status

-

- US Federal List

- No special status

-

- CITES

- No special status

-

- State of Michigan List

- No special status

Contributors

Cynthia Sims Parr (author), University of Michigan-Ann Arbor.

References

Conservation Commission of Missouri, 2002. "Bluegill fishing in Missouri" (On-line). Accessed 26 March 2002 at http://www.conservation.state.mo.us/fish/fishid/bluegill/.

Froese, R., D. Pauly, eds.. 2002. "FishBase: Lepomis macrochirus" (On-line). Accessed 26 March 2002 at http://www.fishbase.org.

Murdy, E., R. Baker, J. Musick. 1997. Fishes of Chesapeake Bay. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Williams, T. 1996. "Fish capsule report: Lepomis macrochirus" (On-line). Accessed 26 March 2002 at http://www.umich.edu/~bio440/fishcapsules96/Lepomis.html.